Service. The word conjures up feelings of utter disdain and stress.

As a fundamental requirement toward graduation, service has slowly become the bane of many students’ existence. Normally, students participate in events such as clean-up trips, tutoring, and outreach programs throughout their high school career to boost a mandatory service portfolio. These activities serve not only to add to students’ service credit, but ideally to transform ISB students into thoughtful, compassionate and resourceful global citizens. That is what service is supposed to do.

But reality is another story. The very mention of service is met with collective groans from a student body constantly reminded of the daunting list of requirements in order to graduate.

A combination of student apathy and over programming conspire to diminish service at ISB.

On paper, ISB is doing everything right. Students are required to complete more service activities as graduation inches closer. While one person may not make a huge impact, as a collective school of people, our efforts to promote and actively help the environment, social justice issues, and the less privileged should be felt, right? Right?

While the work we’re doing as a school is definitely important, the current way service at ISB works leaves plenty to be desired.

First, some students simply don’t care. When talking to my friends at lunch about the service credits I desperately need to get, variations of “I’m honestly doing the bare minimum,” and “I absolutely hate it,” circulate around the table. This is a relatively common phenomenon most students can probably relate to. While there are definitely more passionate students who can carry on about how many service trips they’ve been on, for the quiet majority of us, even writing a reflection on what we’ve learned is a struggle: “Service reflections feel forced to me,” says 10th grader Charisa Howe. “I feel like because they’re required, we write what the teachers want us to say, not our genuine feelings.”

While service may not be the first choice for students in terms of spending their free time, it would be wrong to say students gain nothing from service. For instance, a large part of service is to discover more about yourself and use your skills to help others. French Wongananchai, an alumni from the Class of 2019, describes his experience as president of VOX as “big fun.” It allowed him to indulge in his interest in singing (later leading to his career as a professional) as well as fulfill his service requirements.

This is where service at ISB can be really helpful. Clubs like Pep-band, Theatre Tech, or any of the cultural clubs inherently call for the use of specific skills that allow for a delicate balance of passion with service. But with this, another problem arises. Not every club or service experience enables people to actually use their passions towards a better goal, and so often students goof off or stare at their phones during club meetings.

That’s not to say every service-related activity needs to feel fun, because at the end of the day, service isn’t about us. It’s about helping others and putting effort towards the greater good. But what service needs to be is balanced — something that genuinely allows people to use their skills to make a difference, to leave an impact. Making one poster on Canva over the course of three club meetings or buying candy to sell isn’t students using their skills to help others. It’s not even the bare minimum of people “passionately” helping others, with work in clubs being relegated to another task to be finished and over with.

Additionally, for many, service and the word “interesting” simply do not intersect. “I think those people [who don’t engage in clubs] are kind of annoying,” GSA club officer Shivani Padhi says. “It’s hard to get them to attend meetings, or contribute much,” she says. “When there are larger clubs … some members don’t do much.” Larger clubs tend to have people idle away because there is lack of accountability. With more people to manage, some students talk with their friends or scroll through Instagram instead of engaging.

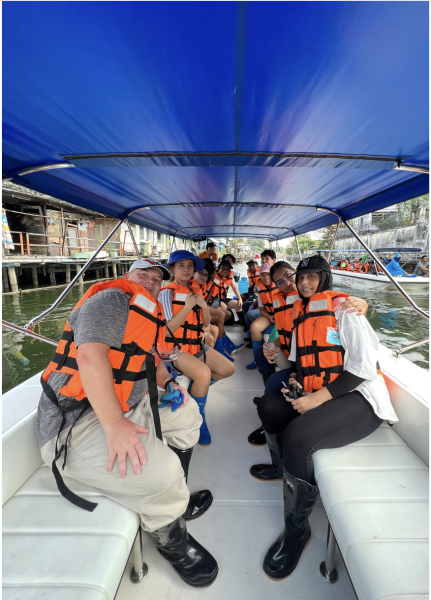

This can be felt on service trips as well. On a Terracycle trip, which was meant to help clean up khlongs, a majority of students were fanning themselves at the side of the boat rather than gathering the garbage in the waterways. Sure, it was hot and sticky and the stench from the khlongs was less than ideal. I’ll even admit I wasn’t all that happy spending my Sunday collecting garbage instead of soaking in the last of the weekend. But the lack of care was acutely evident. Despite this, we all got the credit for the work and we all added it to our service portfolio. Ian Galbraith, the advisor for the Green Panthers club, acknowledges that some people “are definitely checking a box” and “taking full advantage.” He says “it’s more a function of what people are excited by. If people are genuinely interested in cleaning up a khlong, they will go and enthusiastically clean up a khlong.”

Combining apathy with lack of accountability and the passive “hope” that students will be interested in service leads to ISB’s current problem. Students either don’t care or are already over-programmed. And that affects our collective impact. Demanding academic requirements, summative assessments, and extracurriculars all conspire to undermine service. Moreover, going to a club meeting once a week for 25 minutes will never be enough time for students to meaningfully mesh their passions with service. “There is just sort of a default to participating instead of having an impact,” Mr. Galbraith adds.

To be a better school, a school that deserves to proudly flaunt its service achievements, a change for students to take more ownership and more interest in their work is needed. Which can only be achieved if service can become more than ticking a box.

Christopher Bell • Dec 1, 2023 at 9:52 am

This was a very interesting article as you made me think about the service requirement with the quotes at the end of the story.